Cracks in Containerized Development

This article was initially going to be titled “Rant About Developing Software on Immutable Linux,” but the scope continued to increase as I wrote. Fortunately, the much longer first draft was deleted because I forgot to push it to version control before wiping my laptop and installing NixOS, so this version is more concise.

Preface: Immutable Linux

Around spring 2024, I bought a new laptop. My old one had melted its hinges apart and was (quite literally) held together by duct tape. Going into college, I wanted my computer to be as stable as possible, and Linux was non-negotiable. To this end, I decided to install Fedora Silverblue, a distribution of Fedora advertising itself as being pretty much unbreakable.

Silverblue is one of many “Atomic” Linux distributions, others including Vanilla OS, Bazzite, and even ChromeOS. These distributions are atomic/immutable, in that their core system is based on an image and cannot be easily modified to install additional packages. In the case of Silverblue, rpm-ostree is used to handle transactional updates, comparing the local system to the latest upstream commit, exactly like a version control system. Applications are preferably installed as Flatpaks, which are sandboxed from the home system and updated separately, and anything else is supposed to be done using a tool called toolbx (more on this later). Some major advantages of atomic distros is that, unlike traditional Linux systems, they are pretty difficult to break or clutter with unnecessary packages.

Toolboxes

The primary way users of atomic distributions are meant to interact with tools that aren’t available as flatpaks is through toolboxes. These are impermanent-but-not-ephemeral pet containers that can be freely messed with without worrying about polluting your main system. Personally, I loved the idea: One container for each task at hand. I could keep my ros environment separate from my python environment, separate from my node environment, and each of them separate from my main system.

However, there are multiple flaws when it comes to actually using toolboxes to manage development environments.

- Toolbx only works with premade images.

Since most container images are heavily minified for cloud deployment, they often lack basic command line utilities, a prompt, man pages, etc. This means toolbx only works with a set of premade images for specific distros that have had these tools injected back in. It’s unrealistic to set up a new toolbox-ified image for every project you need to work on. And, since it’s equally unrealistic to expect every project to maintain a toolbx compatible image just so some developers on linux can contribute, toolbx is effectively unusable for software development.

- Toolbx always mounts the home directory into your container.

To demonstrate the implications of this on software development, let’s set up a new toolbox.

$ toolbox create rust

$ toolbox enter rustNow, inside the toolbox, let’s install rust via rustup.

$ curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

$ cargo --version

cargo 1.85.1 (d73d2caf9 2024-12-31)Success! Rust is now installed, however, upon returning to your home system, you may notice:

$ cargo --version

cargo 1.85.1 (d73d2caf9 2024-12-31)Uh oh. The rust toolbox is supposed to be isolated from my main system. What gives?

Since the rust toolbox and your home system share the same folder, and rustup installs everything to ~/cargo/bin/ and changes the default bash profile to add that directory to path, your packages get copied over to the main system.

This completely defeats the purpose of a clean and isolated host OS, while keeping development tools in isolated toolboxes. Now that any environment can interact with any other environment, we lose all the benefits of our immutable and pristine core system.

- Every toolbx environment must be set up from scratch.

Let’s say, ignoring the aforementioned issues, your team decides to make a standardized development image for your project that is compatible with toolbx. Aside from adding back core programs, what would be in it? If you ask a contributor that prefers to use vscode remote development capabilities to mount into toolbox environments, they’d say nothing (more on this later). However, if you ask a different contributor, they might want a specific neovim setup installed. A third contributor would then get annoyed that neovim is being installed instead of emacs, and so on. Surely it’s possible to set up a containerized development solution that doesn’t involve pre-installing every possible developer tool?

From toolbx’s failings, we can define a set of criteria for the ideal development setup.

- Projects must be able to define reproducible environments.

- Development environments must be isolated from the host system.

- The system must be editor, tool, and environment agnostic.

From here on, every tool will be examined against these criteria.

Solving Toolbx’s Issues with Distrobox

distrobox is a fork of the original version of toolbx, totalling a monstrous 10,000+ lines of bash. It addresses several of the core usability issues of toolbx. Notably, it has the capability to set up and use any container image, regardless of whether it’s been set up specifically for developer use.

One useful tool distrobox provides is called distrobox-assemble. It allows us to specify our environments in a more declarative manner. Here’s an example configuration for a distrobox environment that installs vim and tmux into a ros base image.

[my_distrobox]

additional_packages="git vim tmux"

image=ros:jazzy

nvidia=true

init_hooks="install_random_stuff_that_isnt_in_apt"

home=/tmp/example_home # isolation!!?As you can see, distrobox lets us set a custom home directory, which somewhat solves the issue of packages polluting our actual home directory.

First, let’s examine how it works with arbitrary container images. When a new distrobox is created, the tool injects a script called distrobox-init to run on first startup. Looking through the source code, we can find:

# Note that this code is licensed under GPL-3.0

# Check if dependencies are met for the script to run.

if [ "${upgrade}" -ne 0 ] ||

[ "${missing_packages}" -ne 0 ] ||

{

[ -n "${container_additional_packages}" ] && [ ! -e /.containersetupdone ]

}; then

# Detect the available package manager

# install minimal dependencies needed to bootstrap the container:

# the same shell that's on the host + ${dependencies}

if command -v apk; then

setup_apk

elif command -v apt-get; then

setup_apt

elif command -v emerge; then

setup_emerge

elif command -v pacman; then

setup_pacman

elif command -v slackpkg; then

setup_slackpkg

elif command -v swupd; then

setup_swupd

elif command -v xbps-install; then

setup_xbps

elif command -v zypper; then

setup_zypper

elif command -v dnf; then

setup_dnf dnf

elif command -v microdnf; then

setup_microdnf

elif command -v yum; then

setup_dnf yum

else

printf "Error: could not find a supported package manager.\n"

printf "Error: could not set up base dependencies.\n"

# Exit as command not found

exit 127

fi

touch /.containersetupdone

fiNow that’s jank.

In order to set up a set of core packages in an arbitrary linux environment, distrobox-assemble will guess which distro it is in and run a corresponding install script.

As you can see, at the cost of very questionable hacks and terrible usability, distrobox comes somewhat closer than toolbx to acheiving our goals.

- [?] Projects must be able to define reproducible environments.

distrobox-assembleprovides rudimentary support for setting up consistent environments from arbitrary1 base images

- [?] Development environments must be isolated from the host system.

- with custom home directories, we can set each box to use

~/distrobox/<name>as its home directory

- with custom home directories, we can set each box to use

- [?] The system must be editor, tool, and environment agnostic.

- theoretically users can use init scripts to install binaries for whatever tools they want into their containers

I was able to use a setup that involved using init scripts to curl a bunch of binaries, add them to path, and clone my editor’s dotfiles in each distrobox for a few months, but surely there’s something better?

Devcontainers

Devcontainers are a more popular way to go about developing software inside a container than toolbx and distrobox. Projects can define metadata according to the (theoretically) editor-agnostic specification, which enables supporting tools to mount the project directory into container environments. This sounds great, and it almost is. However, aside from the de facto implementation being a proprietary vscode extension, there are a few areas that make this specification unfit for the goals we have defined.

- Projects must be able to define reproducible environments.

This one is a slam dunk. Devcontainers’ sole purpose is enabling projects to define consistent container-based development environments. The environment can be just about any container image.

- Development environments must be isolated from the host system.

Since only the project directory is mounted into /workspace inside the container, everything is perfectly isolated from your home system.

- The system must be editor, tool, and environment agnostic.

This is where things get a little silly. Personally, I had an immense amount of difficulty getting vscode’s devcontainer extension to play nice with podman, the default container manager (as opposed to docker) in Silverblue. In fact, since the extension is a proprietary black-box, I ended up having so much difficulty I switched to helix, a much nicer terminal-native editor, in hopes that command line tools would be easier to use inside a devcontainer. Oh boy was I wrong.

The vscode devcontainer extension is not the only implementation of the specification. The devcontainers project, which was spun out of Microsoft in an attempt to make it a cross-editor standard, also maintains a reference cli. I decided I would make a setup that would install my preferred developer tools (helix and zellij) inside each devcontainer, and finally be finished with this pointless journey through container devtools. As it turns out, this is impossible.

The devcontainer spec supports a concept called features, in which custom tools can be added on top of containers. For example, if I wanted to add neovim and zellij to a devcontainer, I would add the following to its devcontainer.json:

"features": {

"ghcr.io/larsnieuwenhuizen/features/neovim:0": {},

"ghcr.io/larsnieuwenhuizen/features/zellij:0": {}

}Wait a minute… the devcontainer.json is a configuration for the project’s environment that everyone will use. This means if a contributor clones a repository and wants to edit it with neovim and zellij, they’re going to have to gitignore their devcontainer.json, or beg upstream to install their preferred tools in everyone’s workspace. This certainly isn’t workable.

But wait again, you don’t have to manually add a vscode-server feature to all your projects. How does Microsoft do it? The answer is that I can’t tell you because I don’t know. VSCode server is proprietary. Presumably, the vscode server binary that vscode installs into the root directory of every container it connects to is completely statically linked, a luxury we do not have in our goal of making arbitrary development environments compatible with arbitrary developer tools.

The next thing I thought of was injecting features into containers. It’s conceivable for a tool to be able to use devcontainers with a set of user-defined additional features. This, too, falls apart if we examine it further.

Examining the source code for the cowsay feature, which installs the cowsay package, we find:

cowsay

├── README.md

├── devcontainer-feature.json

└── install.shThe install.sh script installs a simple cow talking to /usr/local/bin/cowsay, and the devcontainer-feature.json defines the properties of our feature. Inside the json file, we find:

"installsAfter": [

"ghcr.io/devcontainers/features/common-utils"

]It can’t be… surely not… What is in the common-utils feature?

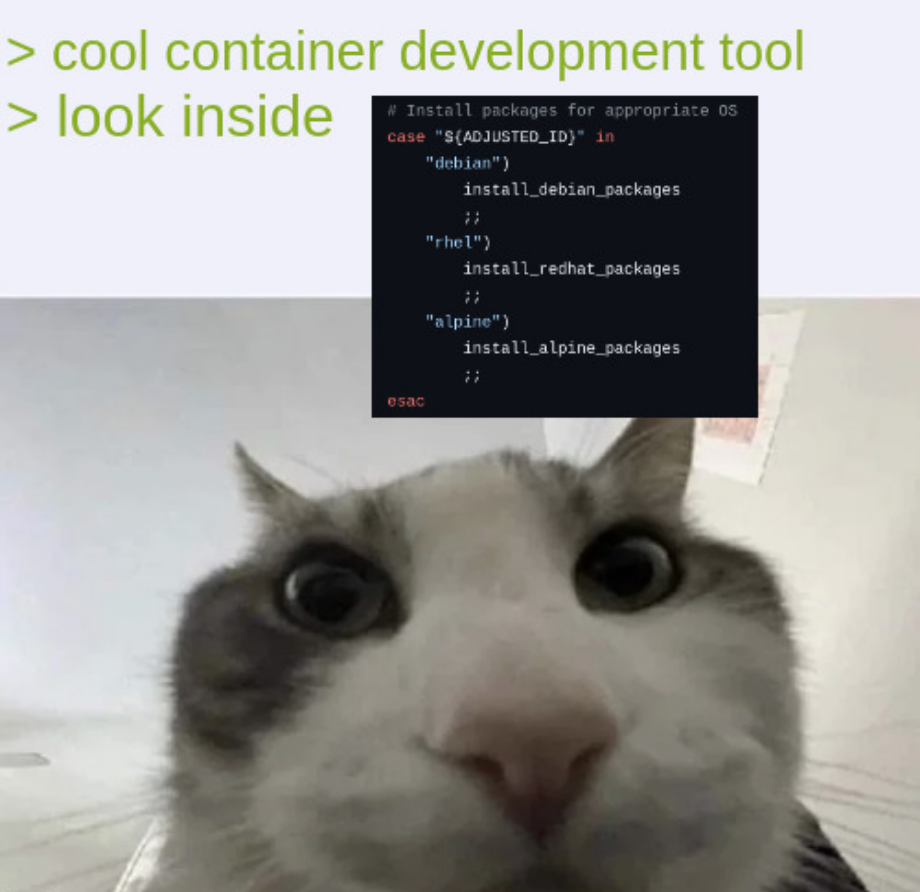

# Install packages for appropriate OS

case "${ADJUSTED_ID}" in

"debian")

install_debian_packages

;;

"rhel")

install_redhat_packages

;;

"alpine")

install_alpine_packages

;;

esac…

A Universal Linux Binary

So now we’re at quite a difficult roadblock. It’s possible to make per-project reproducible environments that are isolated from the home system, 2/3 of our goal, but that last third is unexpectedly difficult. Since developers will want to use arbitrary packages in their development, the problem boils down to “we need to run arbitrary packages inside arbitrary linux environments,” a problem that’s at the very least older than I am.

Like many before me looking at this problem, I was aware of a tool called Nix, but had no clue what it did. I was inclined to dislike it, in no small part due to evangelists. However, while searching for a solution, I came across this article by Mitchell Hashimoto that describes using Nix inside a dockerfile to build an application and then copying the build output into a minimal layer.

Nix has this really cool ability to keep track of a package’s closure. This refers to the package, all of its dependencies, and all the dependencies’ dependencies, recursively. For example, if I build nixpkgs#firefox in a local directory, it will output a result symlink to /nix/store/<hash>-firefox-<version>/. Nix stores every package inside the nix store using a hash, and every package references all of its dependencies via their absolute paths. This enables a lot of awesome things, including multiple versions of the same package and ephemeral shells. Most importantly, for our purposes, it lets us copy the closure of a package (or multiple packages) into a directory.

This inspired me to make something really silly. Feel free to skip this code if you aren’t interested in the details of what it does.

# Uses nix image to build user defined packages and then install them into the

# specified base image

ARG NIX_IMAGE

ARG DEV_IMAGE

FROM $NIX_IMAGE AS builder

# Formatted as "nixpkgs#package1 nixpkgs#package2 etc"

ARG PACKAGES_STRING

# The new nix cli doesn't work without this

RUN echo "experimental-features = nix-command flakes" >> /etc/nix/nix.conf

# Builds packages to ./result, ./result-1, etc

WORKDIR /tmp/build

RUN nix build $PACKAGES_STRING

# Store string containing all the result directories

RUN echo $(find -P . -type l -print) > built_pkg_dirs

# Put closure of all built packages in /tmp/closure

RUN mkdir /tmp/closure

RUN nix copy --to /tmp/closure $(cat built_pkg_dirs)

# Fill profile directory with symlinks to every binary of everyone package that

# were specified to be installed

RUN mkdir /tmp/profile

RUN for package in $(cat built_pkg_dirs); do \

bin_dir="$(readlink $package)/bin"; \

# some packages (eg. manpages) don't have bin directories

if [ -d "$bin_dir" ]; then \

for binary in $bin_dir/*; do \

echo "simlinking $binary"; \

# || true is needed because binary name collisions can occur without

# nix's hashing. any collisions are ignored, since the correct

# library is still installed

ln -s $binary /tmp/profile/$(basename $binary) || true; \

done \

fi \

done

FROM $DEV_IMAGE

COPY --from=builder /tmp/closure /

COPY --from=builder /tmp/profile /yadt-binThis dockerfile installs a user-specified set of packages into a layer on top of an arbitrary dev image, and works regardless of whether the user has installed Nix on their machine.

I made an experimental cli called YADT (Yet Another Developer Tool) as a proof of concept, and it does indeed work. However, discovering Nix also led to me no longer wanting to develop inside containers in the first place. Comparing the two solutions to installing packages, the way Nix works makes significantly more sense from first-principles than container tools. “Ship a package and all of its dependencies” is a simpler approach than “ship my entire machine so this package can run.”

Thanks for reading this far :) I wasted a very unreasonable amount of time thinking about this.

Footnotes

-

Presuming your image has a package manager contained in distrobox-init’s hardcoded set of checks. ↩